Inside a small workshop in the premises of around a century-old house in Srinagar’s Rainawari area, Ghulam Mohiudeen Ahanger, 72, is busy repairing surgical equipment like blood pressure machines, hospital beds, and other such instruments.

In Rainawari, Ahanger lives in Bandook-Khar-Mohalla, a name gained after some people associated with the business of gun production settled here decades ago. Later, the government banned the industry in Kashmir after sighting security reasons. This left these people jobless and forced them to turn to other possible ways of making their ends meet. Among them, some started using their skill to make and repair medical instruments to satisfy their daily needs.

Decades after, Ahanger and his brother continue to carry on their forefather’s legacy and are the only two surviving members of this business. “I have learned this skill from my father and I have been doing this work from past 60 years now,” says Ahanger.

Ahanger and his predecessors hold the name ‘German Khar’ among natives. The story behind the origin of their name German Khar starts in the 1940s after some equipment, originally made in Germany, was brought to their elders by a German national who had failed to repair it anywhere else in the valley. “My father worked on it for several days and repaired it,” said Ahanger. He recalls another incident in which authorities of chest disease hospital in Srinagar approached his grandfather with damaged German-made surgical equipment. His grandfather not only repaired it but also made its replica and was efficient in repairing such machines. Maharaja Hari Singh came to know about their skills of repairing German-made machines and named them as German Khaars- Khaar in the Kashmiri language is blacksmith but is also used for a mechanic.

While mending a machine, Ahanger says, their ancestors came to Kashmir some 300 years ago from a place called Hazara in Afghanistan and settled in a small corner in Rainawari area of Srinagar. Subsequently, people started identifying them as people from Hazara and over the years their locality came to be known as Hazari Bazaar.

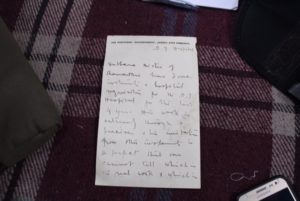

Ghulam Mohiudeen Ahanger also maintains a small wooden closet at his workplace in which he has stored gifts, letters and, other valuable things he terms as ‘memorable’. In it also lies an envelope that covers an old handwritten letter of appreciation which was given to his father in 1940s by a foreign national who used to work in a local hospital here as an administrator under British Raj. The letter is addressed to then Maharja Hari Singh by the administrator in Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) Hospital. It is dated March 27, 1940, and reads “Subhana Mistri of Rainawari has done instruments and hospital requisites for the DG hospital for the last four years. His imitation from other instruments is so perfect that one cannot tell the difference between the real work and the imitated one.”

It further reads. “For a small station like Srinagar to find a man of his precision and intelligence is an acquisition.”

Few houses away, his elder brother works in a small outhouse: The 80-year-old, Abdul Rehman Ahanger, another existing German Khaar. He is presently engaged in making sticks for military men in the valley. “I usually make nameplates, badges, alphabets and other military accessories,” said Abdul Rehman. His son, who supplies military equipment to various army cantonments in the Valley, helps secure some assignment for his father from the soldiers of Indian armed forces.

Rehman recalls that in older days they would work in a big workshop on the ground floor of their house. “We were seven brothers working together in that workshop as we used to get a lot of work and at times relatives would also join to work with us,” Rehman said with a glum face.

Mohideen added to Rehman’s reminisces and said that around 20 people would work in the workshop at that time. His elder brother Ghulam Mohammad Ahanger would lead the workshop during that time as he was much famous for his dexterity. But later he died a tragic death.

“During 1990s in Fateh Kadal area of Srinagar our brother suffered a brain haemorrhage after an armed soldier stood right in front of him and pointed his machine gun towards him,” said Ghulam Mohideen while adding, “soon, he was admitted to a local government hospital for treatment where he died on the third day of his treatment.”

Later, the brothers split and started working separately. “Until the time he was alive, he guided all of us like a father. We would never ask him to pay us for our labour. We used to live together and all the customers would give the money to him and he was responsible for feeding every family member and fulfilling their needs. We never craved money as we were getting everything we wanted. He never left us alone. Such was his stature. I pray to God to reunite us again in the hereafter,” he added.

Later in life, Mohiudeen was lucky to travel to Mecca for Haj Pilgrimage where he even got a chance to show his skills at a hospital where he had gone with his wife for her treatment.

“I met a Kashmiri doctor there who had trouble treating his patients as some oxygen machines were not running well. I offered my help. At first, he was reluctant but after knowing my background he accepted to take my help. I repaired all of them which impressed the hospital authorities who in return wanted to pay me for my service but I refused. They thanked and also treated my wife for free and with her the other Kashmiris who accompanied us,” he recalled.

Earlier Ahangar brothers would get a lot of work but from the past few years, there has been a drastic decline. “The reasons are obvious as the world has witnessed a huge change in technology as most of the machines which were controlled manually are automatic nowadays,” Mohiudeen says.

Being left with less work in their old age, the duo spends hours in their workshops and take days to repair a single machine.

“I only make around 50 rupees a day as people prefer to get machines repaired from well-equipped mechanics and engineers” he added, “ sometimes I don’t have work and I sit here understanding the mechanics of new-age machines.

Ghulam Mohiudeen is survived by his wife, daughter and son, Bilal Ahmad, who is a teacher by profession. “My son, Bilal, is not interested in this work as it generates very less income and requires a lot of patience and hard work. ” he said while adding, “Today’s generation does not have the patience to learn this craft. But we will carry on, our work is our identity.”