By Sarah Lina Ewald and Tavseef Mairaj

Six years ago, David’s life changed considerably during a six-month long work-related stint in Canada. Inspired by the athleticism of his co-workers, he decided to take up bicycling like them. Back in Germany, he stopped driving around in his car and gave up smoking. “I have mainly been riding a bicycle since then. I bike 20 km daily, to the office and back home. I see this as my contribution to a cleaner environment and hope more people will decide to drive less by car and rely more on their own muscle strength,” David tells us when we meet him in Nishat, Srinagar.

When a planned vacation with some friends did not materialize, he decided to hop on his two-wheeler and take a long bicycle trip alone. “While driving from Germany via France to the Mediterranean Sea, people were kind and offered supplies and hospitality. When I climbed the last hills of the Esterel Mountains and saw the sea unfolding before my eyes, the sight gave me goosebumps. At that instant, I knew I wanted to travel around the world on a bicycle.” The rest, as the cliché goes, is history (in the making)!

One afternoon, David was caught in the middle of a heavy sandstorm in Dasht-e-Kawir in Iran. Only after two hours was he able to find a little shack for shelter. The next day, he reached an oasis. “I parked my bicycle and started looking around for people. In the meantime, three dogs found my biscuits in the outer bags attached to the carriers and finished them off. In exchange, one of them agreed to guard my bicycle overnight,” he says, smiling.

“On a journey, when you have set a goal for yourself; you’ll be all the more satisfied if you can reach it through your own strength. Besides that, often the way becomes the true destination,” he told us. David was 30 when he made this decision. To save money to realize his dream, he worked hard for three years, often on multiple jobs. “Sometimes it became really depressing, doing nothing else but work. Yet, the last few months have really compensated for all that time.”

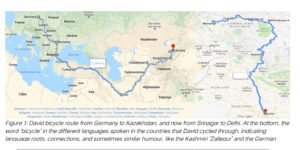

His journey started from the city of Neuss in Germany. It took him around 180 days to bicycle 10,000 km to Almaty, Kazakhstan. From there, instead of pedalling on along the Northern Silk Route to Urumqi and beyond (Beijing), his journey came to an abrupt halt because he had to visit Kashmir. When asked about his decision to come to the Kleines Tal despite the associated negative publicity, David says that it was always on his wish list.

“I think three years are enough to do the research and planning. One day I stumbled upon a few photos from Kashmir and knew I had to visit this place. What I’ve learned during this 11,000-odd km journey is that no matter how difficult a situation might appear to you, somehow there is always a way. Just don’t think too much, or get lost in unnecessary questions. The world is not as dangerous as you might be led to believe sometimes. It is beautiful and full of wonderful people.”

Despite the bravado embedded in that statement, David did not cross over onto the Southern Silk Route because he did not want to take the risk of travelling through Afghanistan. He also knew that if he wanted to reach Kashmir, travelling through Pakistan would not be hassle-free because of the border restrictions between India and Pakistan. So he flew from Almaty to New Delhi and from there to Srinagar.

So far, the tour has led him through 15 countries. One of the things he likes about his chosen mode of commuting is experiencing the world more leisurely and intensely. “On a bicycle, you are not too slow, but also not too fast. You do not zoom past the details of a place like you would in a car, for example. People are more welcoming of bicycle-riders, perhaps because they seem to be less intrusive. You greet and meet more people. If you get lucky, they might give you insider tips about a place. This often leads you to small beautiful nooks which may not necessarily be touristy.”

Nowadays, tourism has become a major economic activity worldwide. Most tourist spots are secluded and sparsely populated. One reason for this could be that the ecology of these places cannot sustain large numbers of people. But modern tourism, in a mad rush to enjoy city-like amenities in distant mountains and secluded sea shores, brings with it irreversible ecological degradation and conflict between the high-flying tourists and the local residents. Around 8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions emanate from tourism. David’s way of travelling presents a worthy alternative—self-sufficient, non-polluting, gentle and leisurely.

The longest day of the journey, and also the hottest at 42°C, was in Turkmenistan; David had bicycled 167 kilometres in a single day to reach the crater of Derweze in the Karakum Desert. After the geological drilling in 1971 opened an underground cave emitting methane gas, the authorities set it on fire, calculating that all the gas would be burned out in a few days. It is aflame to this day, earning the moniker “jähenneme acylan gapy” (Gate to Hell) from the locals! “During the night, the scenery was just breathtaking,” David adds.

An equally important lesson from his journey has been regarding the choking of the silk routes. Once upon a time, the silk routes used to be the lifeline of the world, connecting Far East with Central Asia, Middle East and Europe. Kashmir was at the centre of this trade–and-culture lifeline of the world. On the other hand, people from Kashmir used to travel to Peshawar, Kabul, Samarkand, and even to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina for Haj, on foot or on horseback. Now Kashmir has become a cul de sac, a place that leads nowhere, literally and metaphorically. Kashmir has always been surrounded by high mountains which allow only the most committed to pass over them. But even a bicycle (of a person as determined as David) cannot cross the political mountains that now cage us.

From Kashmir, David plans to travel for two more years, with China as the next country on his list. A pan-American cycling trip is also in the itinerary. He says that if he has “money left at the end”, he might make a trip to Africa as well. Ultimately, he aims to arrive back where it all started, i.e., Neuss.